4 channel video installation, 2021.

I start with the sound. In the first seconds I think: This could be the beginning of a song by the band Roxy Music, a few seconds later I think of Sacre du Printemps. Maybe that’s not a bad start to talk about Sam Gora’s work, because already sound-wise this sets up a telling contrast between romantic soft-knees-through-straight-men’s-voice-proto-new-wave reminiscences on the one hand and shrill dissonant flutes announcing that the virgin will be sacrificed to the god of spring, dancing herself to death for it on the other. Male desire versus male punishment. The synthetic cajoling reverb is quickly over, the shrill flutes are soon joined by ominously low frequencies that go straight to the gut and to fear. Somewhere between construction site and war.

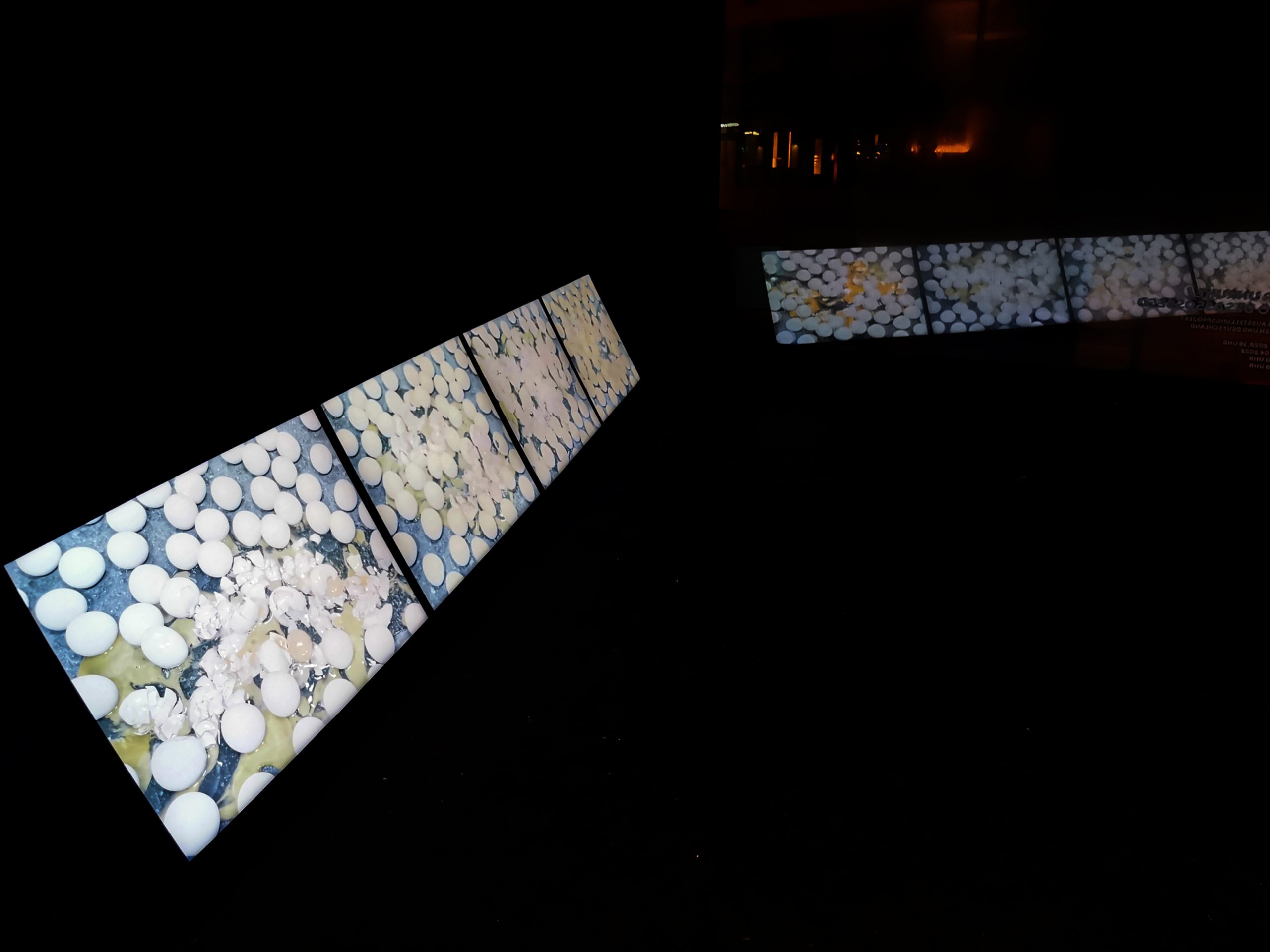

This matches the visuals of the installation: four cold monitors stand on a dark gray pile of rubble, about the size of a grave mound as seen in movies when the ground is too hard to dig deep enough – a molehill at human length, so to speak.

While the music successively increases in drama, the screens turn on, one after the other. On the screens you can see a lot of eggs spread out on the floor. Probably the most universal symbol of life, multiplied in the virtual space of the screens, directly above the dead pile of rubble. But to build such glittering electronic machines as if from another star, children have to extract minerals in mines.

A woman’s foot is trying to gain a foothold. Where is she supposed to step? There is no space for her. Carefully groping she puts her foot on, eggs start to burst. So it goes on, or rather she goes on. However, she has two feet, and while she continues, in the installation from one screen to the next, there is a strange intermediate stage: we see only one foot hanging in the air. Haltless. Briefly, I think of images of people who have been hanged. But she continues walking. The caution with which she walks can also be read as a deliberate crushing of eggs. There is always a moment when I marvel at how much resistance a small egg offers to the foot. Then it breaks. The destroyed eggs leave traces on the floor and on the woman’s foot. While in the beginning the steps are tight, later the step shapes vary, a bit like in a ballet. But after she goes through the egg screens once, they turn off one after the other. It’s as if something is dying. Will the traces of the woman’s path be erased so quickly? The music echoes.

The title You Go, Girl! is ambiguous: initially used as a “cool” slogan to encourage a woman, the phrase is now considered more of an empty phrase. It’s an interesting question, however, why the Urban Dictionary, for example, devalues the exclamation as a cliché. Is the dictionary sexist, or is it an appropriate diagnosis of the fact that the saying often remains empty because women continue to have obstacles (eggs) thrown in their path all the time? But it can also be interpreted as a command. Go on! Go do it! Meanwhile, in addition to the gender pay gap, there is also the term stress gap, because women are drilled to think that they are never enough. That they of course do reproductive labor unpaid or underpaid, and this is especially true for PoC and women who don’t fit the heteronormative model. Socially, men still have the monopoly on recognition. Because women who are successful are often enough publicly punished for it. Eggs burst like dreams. Women are blamed for being successful and for not being successful. For conforming to role models and for not conforming to them.

There is a long tradition of mermaid myths. In the Danish fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen, the mermaid is punished for her sexual desire, or more precisely, for actively pursuing her desire. She loses her voice, and in return she gets two legs, but every step hurts as if she were walking on broken glass, or also: “Every step she took was, as the witch had told her in advance, as if she were stepping on sharp needles and sharp knives; but she endured that gladly…” She can be saved only, of course, if the prince loves her. However, nothing comes of it and she turns into sea foam.

In China, especially small women’s feet, called lotus feet, were considered the ideal of beauty until the 20th century. The women’s foot bones were irreparably broken and their feet were bound in such a way that they could never walk properly again. The ideal measurement was considered to be feet with a length of ten centimeters. Men found this walk sexy. Since ancient times, it was considered a civil privilege to wear shoes; slaves had to go barefoot.

The work You Go, Girl! also refers to the performance Entrevidas by the Brazilian artist Anna Maria Maiolino from the final phase of the Brazilian dictatorship. In the video, a man gropes his way across a square full of eggs with his eyes closed. All the eggs remain intact, but he walks very slowly, there is also enough space to push the eggs aside. The fear of missing out becomes palpable. What happens in dictatorship when you don’t walk as you are ordered? At Sam Gora, the ground is too full for that. Is the situation hopeless? Not necessarily. After all, it’s a statement to break eggs as long as she wants it that way. She steps into life. And it leaves traces. The performer in Maiolino, on the other hand, remains between lives, between the living eggs, but also between the lives unlived in the dictatorship. The intermediate limbo between the frames at Gora gives hope as well. Also: in the end, she gets out. Who knows where she goes.

Heidi Salaverría (philosopher and art historian)